Chapter 8: Tradeoffs in the Five Ways of Specializing

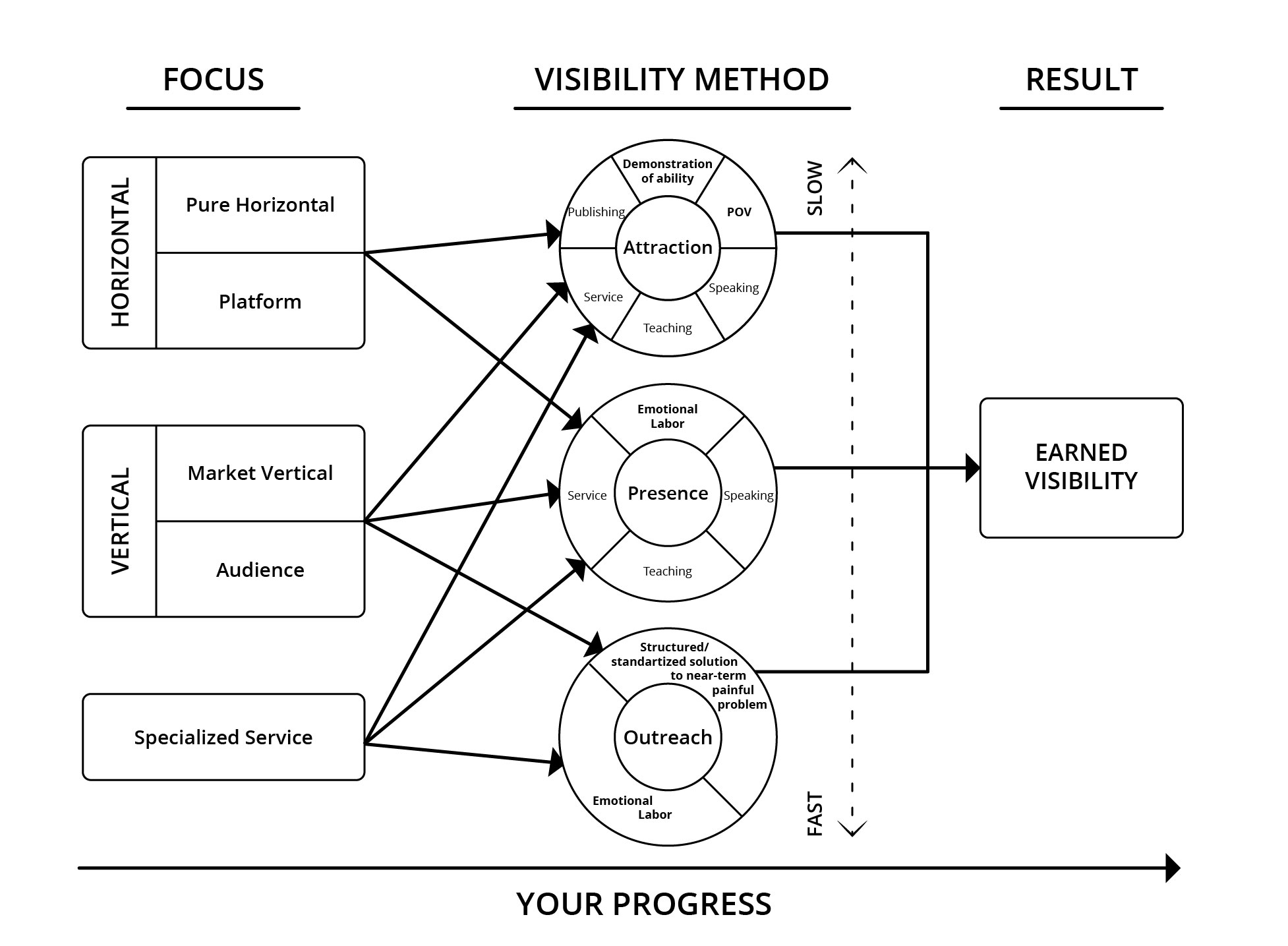

If you want to use specialization to enhance your ability to earn visibility, you'll need to choose a specialization approach.

You might find that one of the five specialization approaches is an obvious fit for your business. If so, great! Go with it. Don't waste any more time doing book learning, because you need to start learning by doing. Motion generates information, and I'm not talking about the motion of flipping pages in this book.

If the idea of specializing still feels risky, then heed that gut feeling and explore the tradeoffs that each specialization approach poses.

You already know about the core risks of a platform specialization; the platform ecosystem will commoditize faster than you can evolve from an innovation business to an efficient business, or you won't want to make that shift so the platform ecosystem will become inhospitable to your innovation business.

Let's look at the benefits and risks of vertical and horizontal specialization.

Vertical Specialization Benefits

It's relatively easy . Check out the LinkedIn advanced search feature. The list of industries there doesn't map perfectly to the NAICS list I linked you to earlier, but it's close enough to make finding prospective buyers pretty trivial, at least for a pure vertical focus.

This makes earning visibility through outbound methods easier as well. Your marketing message is also probably easier to figure out. A typical example will be moving from describing your business using language like “elegant solutions to complex problems” to something like “custom software for retail financial services”.

Word of mouth tends to spread most readily in a vertical fashion . It's kind of obvious, but I'll say it anyway: people in the same industry tend to interact with others in . . . the same industry. From conferences to industry publications to asking a colleague at a different company for a recommendation, word of mouth spreads most readily in a vertical fashion.

You've probably heard of “not invented here” syndrome. This tends to exist most heavily at the boundary between really different verticals. If you work in the finance industry and need to solve a high-speed trading problem, would you ask for a consultant recommendation from a colleague who works in the food and beverage industry? Probably not.

Past clients who leave their employer are most likely to land at a new employer in the same vertical . They can take you with them or at least open doors for you at their new employer. This helps you "stack" related experience more readily.

Note

I distinguish between so-called Creatives, which generally refers to designers, copywriters, etc., and the broader way in which consultants use creativity to solve problems. I think of readers of this book as creative people, even if you don't identify as a so-called Creative.

It's unsexy and downright unappealing to lots of creative types . [23] If you're not put off by the unsexieness of it, that very unsexieness is a barrier to competition, but on the flip side, you might just not be able to imagine how focusing on a single vertical could possibly lead to an interesting career. You're probably wrong, but I get it.

On its surface, it does seem like a limiting choice, but if you've never gone beyond a surface level of expertise, I can understand how you'd have trouble seeing the richness that lies beneath. It's like seeing a small, plain-looking mouth of a cave and not knowing that what actually lies beyond the mouth of the cave is a fascinating, complex system of caverns, sparkling with jewel-like mineral formations. Most vertical specializations will be just as interesting if you go deep enough.

It can be easier to forge strategic partnerships with other firms practicing different disciplines (marketing, accounting, law, etc.) specialized in the same vertical, super-connectors within the vertical (podcasters, associations, conference organizers, etc.), and product vendors like specialized SaaSes, etc.

It shortens the growth path from skill to expertise and from implementor to advisor. By serving a group of businesses that have a lot in common, you will find more opportunity and incentive to become conversant in what's important to the business, allowing you to quickly learn how to create real impact in the context of that vertical.

Vertical Specialization Risks

Not every vertical is equally receptive to outsiders . If you're truly an outsider to a vertical, trying to specialize in that vertical is a risk you should measure carefully.

Verticals can suffer business downturns that are localized to that vertical . 2007 would have been a pretty bad year for anyone to specialize in the real estate, mortgage, or construction verticals. The economic pain that ramped up in 2008 was more widespread than just those verticals, but they certainly were ground zero for a lot of economic carnage, and a service provider unlucky enough to get excited about specialization and then decide to specialize in serving one of those verticals at that time would have been in for a rough ride.

Vertical specialization ultimately requires you care about financial results, people, or business as much or more than you care about your technical skill set. For some folks, this will be no problem. In fact, it will increase enjoyment of their work. The ability to converse intelligently with their clients about the personalities, power dynamics, relationships, and culture of their business along with industry trends and the specifics of competitors is a powerful way for these folks to deepen the impact their technical skills create, and they'll love every minute of this advisor-level role.

However, others will find these exact same things a distracting nuisance and would rather focus on pure technical depth rather than acquire deeper knowledge of their client's business. These folks should probably avoid vertical specialization in favor of something horizontal in nature.

It is possible—though very unlikely—that if you pursue a vertical specialization, you will find client-side concerns about conflicts of interest (CoI). I can count on one hand the number of vertically specialized clients I've worked with who have actually had CoI concerns raised by their prospects.

Note

24: A good resource on the late-sale flip from excited to cautious is this article from Blair Enns: https://www.winwithoutpitching.com/reassuring-words/

If you do have a prospective client voice this concern, there's an 80 percent chance it's actually a late-stage sales objection or an attempt to prevent buyer's remorse. Their mindset has moved from excited to cautious, [24] and they're now playing devil's advocate and trying to de-risk an opportunity they were previously excited about. As they do, they'll turn over every rock and leaf looking for a reason the proposed engagement might be a bad idea. A baseless CoI concern might surface, but if you're prepared for it, you can most likely defuse it.

There's a very small chance that CoI is a real issue. Bigger organizations can internally firewall teams to prevent this, but as a soloist or very small company, it's often not possible to do this firewalling, so you may have to just walk away from opportunities where there is a genuine CoI concern. In reality, however, these situations are uncommon.

Horizontal Specialization Benefits

It's more naturally compatible with how consultants think . If you think in terms of process, frameworks, or any form of abstraction, then horizontal specialization is more naturally compatible with how you think than vertical specialization. Horizontal specialization seems to promise a lot of flexibility in who you work for and where you get to apply your process or framework, and that matches how most consultants are used to thinking.

It's easier for the typical consultant to imagine how horizontal specialization will remain an interesting, deep challenge for them over time. While it's not actually true that horizontal is inherently more interesting than vertical, it seems to be true because of the aforementioned way that you are used to thinking about things. This lowers the emotional barriers for consultants to enter a horizontal market position.

There are so many experiential aspects to what it's like to be an in-demand specialist that it's hard to convince "unbelievers" that vertical specialization can be just as interesting as horizontal, but I promise you, it can. To be fair, it can be if it's compatible with your personality and where you want to take your career.

I'm not sure I can prove this, but I believe horizontal specialization (or a very narrow horizontal focus coupled with a somewhat broader vertical focus) is a more suitable specialization model for the so-called "lone wolves," meaning solo consultants who have no desire to build a team or agency business. This is because the pure vertical focus generally deploys a broader discipline (i.e., marketing, management consulting, custom software development) to a specific vertical. The breadth of the discipline itself benefits from a team of people with a blend of capabilities.

Horizontal Specialization Risks

It can require more work, lead time/runway, and marketing sophistication to find clients . One of the most fundamental differences between vertical and horizontal specialization is the relative absence of external signals of buying intent from the latter. To illustrate this, let's compare how two different specialists might earn visibility trust with prospective clients:

- Juliette specializes in marketing for franchises. This is a vertical focus; specifically, an audience focus. Her marketing can be as simple as reaching out to franchises (they're easy to find because their business model is clearly externally visible) and saying a version of this: "Hi! I have no idea if you have an expert in franchise marketing working with you already, but if you don't—or if your current agency doesn't understand franchises as well as you'd like—we should talk. I've been specializing in marketing for franchises for years now and I'm sure I could bring some fresh ideas and depth of experience to move the needle for you. Again, if you've already got this covered, I'm really happy to hear that and please excuse the interruption, but if you don't have this covered and want to talk, I'd be happy to connect."

Juliette will almost certainly invest in other forms of marketing like content marketing, speaking, and so on. But, if all she had was a list of email addresses for CMOs at 500 franchises and the email copy above, I'd bet real money on her landing a few exploratory sales conversations from that email list, that email message, and a bit of persistent, polite follow-up.

- Mike specializes in infrastructure and application monitoring. This is a horizontal specialization; specifically, a pure horizontal specialization. He's not a platform specialist because he's not focused on a single tool; he's focused on the business problem of using monitoring to move some desirable needle-like application availability.

Note

25: He told me as much in this interview: https://consultingpipelinepodcast.com/121

26: These are also all Attraction visibility methods.

How does Mike connect and build trust with prospective clients? Let's imagine he uses Juliette's approach and cold emails CIOs with an approach similar to Juliette's. The reality is, he's going to get nowhere. [25] What does work for him?

Writing an O'Reilly Media book on his area of expertise, launching and editing a popular weekly email list on the subject of monitoring, and conference speaking have been far more effective lead generation approaches for Mike. [26] This is what I mean when I say a horizontal specialization can require more patience and skill in marketing.

You may be in for a longer sales cycle or an unpredictable/heterogeneous sales process . Horizontal specialists often (but not always) specialize in business problems that are somewhat idiosyncratic. That's what makes them opportunities! The client hasn't developed an internal capacity to handle the problem, few other service providers have the nose for opportunity and risk tolerance required to specialize in this same way, and the problem is not a routine, ongoing thing your client wants to outsource.

If you're an agency selling marketing services, you can integrate with a somewhat standard process your client has for selecting and purchasing your services. But if you're like Mike, solving a problem in the above example, there's almost certainly no standardized process for working with a monitoring expert. As a result, the sales process is going to be much more improvised, at least on the client side. This can be good or bad. It's good if your buyer has the authority to say, "Just make this happen. I can authorize payment myself." You've just bypassed a normally time-consuming process and closed a deal with a few conversations. But if you have to crawl an opaque web of decision makers or are dealing with a buyer who can't just cut a check without higher-up approval, then it's problematic that there's no standard purchasing process. You have to feel your way through a dimly-lit landscape of stakeholders and approval, and that landscape might not look at all like the next client where you have to feel your way through a different landscape, adding time and effort (cost, really) to the sale.

This potentially more difficult, complex sales process can be worth it if the problem you solve is important and is urgently felt by your clients. I'm not arguing for or against horizontal specialization here, just trying to alert you to something that may become a fact of life if you specialize in this way.

It can be easy to confuse the technical difficulty of the solution with the economic value of the solution . This one is insidious, and leads to disappointing situations that seem like great ways of specializing that do actually lead to some increased visibility, but then lead to little business opportunity.

It's so easy for you to see how difficult some problems are to solve and conflate the difficulty of solving the problem with the economic value of solving that problem. It's also easy to evaluate the economic value of solving a problem from your perspective as an outsider and not from the perspective of a business.

Businesses do seemingly dumb stuff all the time. Some of it actually is dumb. After all, not all businesses succeed, and sometimes their lack of success is due to truly dumb decisions. But sometimes business do "dumb" things for smart reasons, and sometimes those "dumb" things lead to positive outcomes for the business.

Maybe they operate in a regulated environment and do stuff that's technically dumb (i.e., paper records instead of electronic) because of the demands of regulation, and the cost of regulatory risk or noncompliance is actually far higher than the cost of the "dumb" thing they're doing. A consultant at the superficial level of expertise sees this situation and thinks it's wasteful, inefficient, and shortsighted. A consultant operating from deeper expertise sees the same situation and understands the context that makes the "dumb" decision the right decision.

The antidote here is simple but not easy. Learn to see things from both your perspective and your client's perspective, and gain enough insight into their perspective that you can almost read their mind. If you can make use of their worldview almost as fluently as your own, you'll be able to understand what problems could make for an economically viable pure horizontal specialization.

There is a special case here, which usually takes the form of developing specialized horizontal expertise that very few businesses would pay consulting rates to access, but a lot of your peers will individually pay small but collectively significant amounts of money to access.

Here's a good example from the world of tech. Adrian Rosebrock teaches developers how to integrate computer vision into Python. This isn't the exact situation I describe above, but it's close because Adrian has chosen to focus his business on individual devs more than large companies. Even if few businesses would pay consulting rates to access Adrian's expertise, a lot of his peers pay an individually small—but collectively significant—amount of money for that access.

Note

27: In the best scenario, you get paid twice; once for the training and then a second time in the form of credibility, access, or both to corporate buyers.

This model works because instead of trying to sell expertise that few businesses demand, you "aggregate" the market demand for that expertise coming from your peers and sell your expertise to them in the form of training, coaching, mentoring, etc. Doing this often gets you corporate clients anyway, but it's a second-order effect of being successful in selling training to individuals who then become sort of like an unpaid sales team for you. [27]

You're smart, so I trust you've seen that no form of specialization is risk-free, and none is an all-you-can-eat buffet of benefits. It's tradeoffs all the way down.

Info

- An LLM-generated summary of this book can be found here: LLM-Generated Summary Of TPMfIC

- If you'd like to chat with this book as an OpenAI GPT: https://chat.openai.com/g/g-Ct18XsNSI-indie-consultant-specialization-gpt

- If you would prefer to read this book in Amazon's Kindle ecosystem, or in print: https://a.co/d/aQztpSK

- If you would prefer a DRM-free EPUB copy of this book: https://philipmorgan.lemonsqueezy.com/checkout/buy/06f1179b-3e4a-4e63-a4ee-08c9f166fc34

- If you want to join my email list: https://opportunitylabs.beehiiv.com//)