Chapter 13: A Model for Earning Trust

We now have enough observation to put together a model of how trust-earning works.

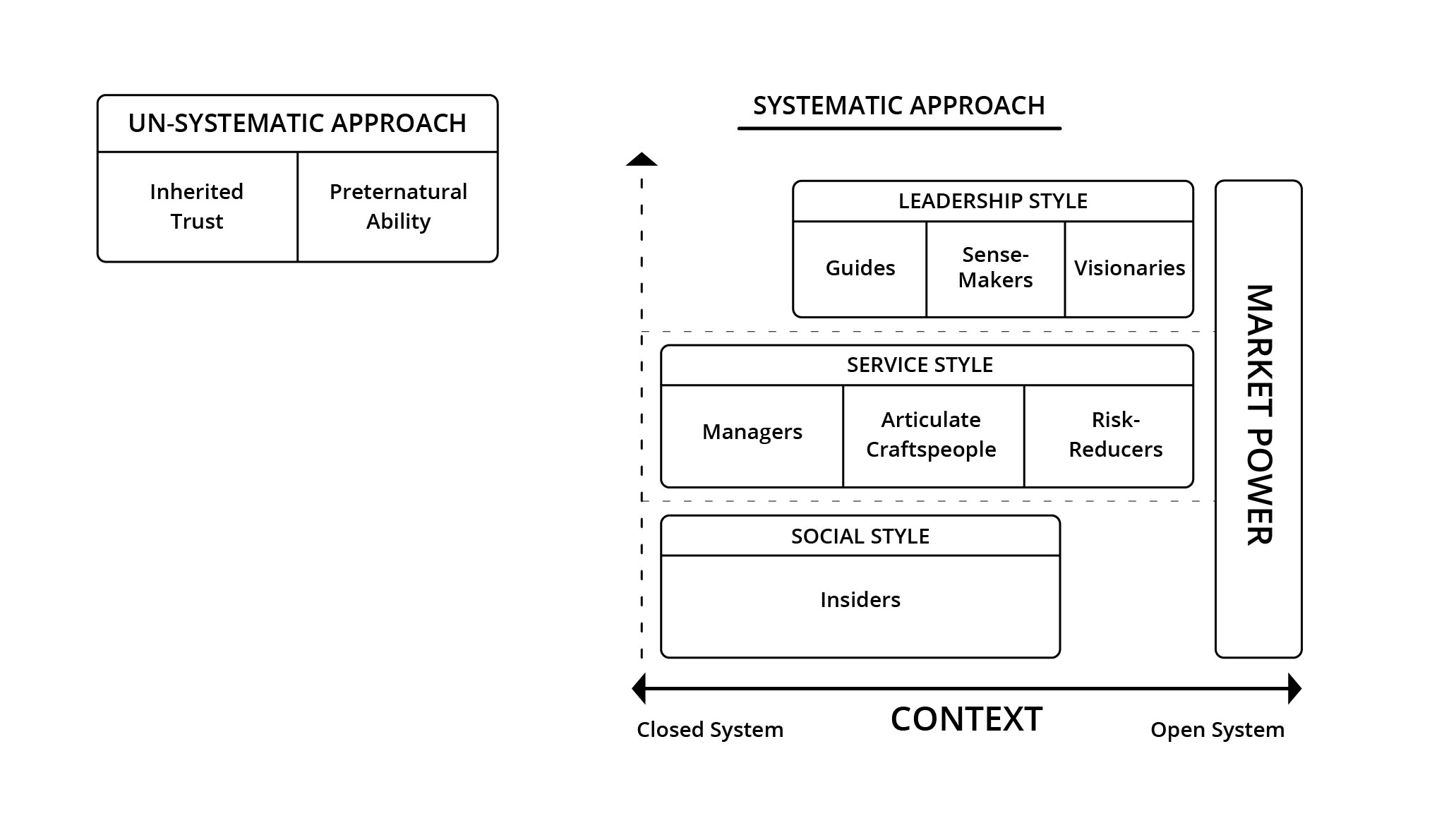

Inheriting trust or possessing preternatural ability are nice. They are also unsystematic approaches that can't be replicated by normal people—us.

We "normals" have access to three systematic approaches—things we can decide to do, learn to do, and implement with a normal allocation of skill and resources.

We can use social connections to earn trust. We can be of service. Or we can lead.

The Social Styles of Trust-Earning

You'll remember that earlier I referenced several forms of affinity that help some consultants become an insider to their clients' world:

-

Shared experience(s)/background

-

Shared social group membership

-

Shared jargon

-

Shared culture

-

Shared worldview

-

Shared social status

-

Shared enemies

-

Shared authorities

These are all primarily social styles of trust-earning. You'll also notice in our model that social styles have the least market power and, while they are effective across most of the spectrum, from closed to open systems, they are not effective in the most open of open systems.

Note

35: George E. P. Box popularized this idea in the easily remembered form I've borrowed here.

This is a good place to remind you that all models are wrong, but good models are useful anyway. [35] I think our model for trust-earning is a good model, but bear in mind that reality is more fuzzy and fluid than this model depicts. Precise, clear lines in the model are simplified representations of the fuzzy, permeable membranes of real life.

So when you see the box that represents the social styles of leadership extending only about 75 percent of the way toward the right end of the closed <—> open systems spectrum, I'm suggesting an observed norm, not an ironclad rule. The norm is this: in the most open of open systems, things are so chaotic and fast moving that the social relationships underpinning the social styles of trust-earning simply don't have time to form. In a fast-moving open system, everybody is a newcomer and everybody is, in a relative sense, a stranger to each other.

This doesn't mean that social styles of trust-earning are completely ineffective in the most open of open systems. Instead, it means the social styles are relatively less valuable; less useful for earning trust that you don't already have. This model is focused on how context (open versus closed systems) and relative value (market power) relate to various styles of trust-earning.

The Market Power versus the Actual Value of Trust

It's natural to see social styles of trust-earning as an easy, beginner-friendly entry point to the world of systematic trust-earning, but it's more complex than that. I have a friend who runs a marketing agency. He makes more money than I do and has a more outwardly impressive business than I do. His website is nicer. On the other hand, I spend more time on stages delivering presentations where I'm trying to lead my market someplace new. I play the role of the visionary.

My friend earns trust primary through social styles. He rarely gets on a stage and does not play the role of the visionary. What gives? I'm engaging in a style of trust-earning that has more market power. Why is his business financially outperforming mine?

Note

36: And I have been in the exact same situation with this friend multiple times.

Context, baby! My friend is very good at using social trust-earning styles in a systematic way. He learns where his best prospects hang out, buys a ticket to those events, and then uses his naturally gregarious, extroverted personality to build trusting relationships with other attendees. I, in the exact same situation, [36] would keep to myself and walk away from the event with almost no new useful relationships to nurture into clients. I'm an aloof introvert, and while I can use social trust-earning styles, I need a small group, intimate context in order to succeed at this style of trust-earning. Additionally, it is in every way easier for me to get on a stage and deliver a visionary talk than to sit in the audience and build relationships with other attendees.

My friend sells services that produce nearly immediate value for his clients; mine take time to produce value. His services fit into a well-defined genre that companies are used to purchasing; mine do not. And so my friend has created a system that produces exceptional revenue quickly; I am doing something more like cloud-seeding to produce exceptional revenue later.

The point of this story is to illustrate how my friend uses a style of trust-earning that has less market power than mine to produce more short-term revenue than I do. Maybe I will ultimately out-earn my friend. That remains to be seen. The point: market power is not immediately and directly correlated to the revenue potential of your business. Market power, in our trust-earning model, is connected to the notions of thought leadership or authority and should be noted that while these are sources of power, their pursuit also entails risk and their monetization may be more difficult.

Does my friend wish he could use trust-building styles that have more market power? Nope! He has built a business with a harmonious relationship between who it's focused on, what it does for them, and how it earns trust, and he's optimized that business for exceptional profitability. Given that context, why would he invest in a riskier trust-earning style?

The model for trust-earning I'm presenting here is not a map of a journey. You don't start at the bottom (social styles) and climb your way to the top (leadership). You will have personal reasons (your personality, comfort zone, etc.) for starting with—and possibly sticking with—a particular style of trust-earning. You may have strategic reasons for shifting that style. But you're very unlikely to use all styles at once or to climb from the bottom to the top of this range of styles.

The Service Styles of Trust-Earning

Being of service can earn trust, but in these cases, what we actually seem to be trusting is the competence and reliability that underpin that service. It's convenient, however, to group the managers, the articulate craftspeople, and the risk reducers together into the trust-earning style of service .

"Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things."

Peter Drucker

I wonder if those who identify as managers feel like Drucker is insulting them somehow. I also wonder if they are relieved not to be burdened with figuring out the right thing to do. That's my oblique confession to not really knowing how managers think in a sufficiently detailed way. But like you, when I observe the landscape of trust-earning, I can see a place where being a good manager is a great way to earn trust from consulting prospects.

"The managers"—meaning the larger group of those who make sure things get done the right way, not just the smaller group of those who have the word manager in their job title—earn trust through their service. They do these sorts of things:

-

Explain how to do specific tasks or projects in a way that works reasonably well. They use media like blog articles, YouTube videos, podcast guest appearances, and talks from a stage.

-

Build up reusable or broadly applicable forms of best practice as the system they operate within commoditizes (moves from chaos to order).

-

Create a feeling of safety by generally furthering the chaos -> order progression of the system they operate within.

The management style of trust-building thrives in closed systems because those systems generally feature the least amount of change and novelty, so our managers are able to articulate their process-based, detail-oriented expertise with the least amount of compromise and caveating, and so are able to apply that expertise with a higher probability of success.

We can think of the risk reducers as managers who are more comfortable and adept at operating within the more chaotic and fast-moving open systems. Instead of detailed, expensive-to-change process documents, for example, we see them using lean or agile methods to reduce the inevitable cost of change present in extremely open systems. Instead of sharing recipes, we see them sharing frameworks.

The articulate craftspeople are more doers than managers, but they still have at least a genuine respect for—if not a deep love for—the process and control needed to produce excellent results with consistency. Their personal sense of identity springs more from the beauty or functionality of the work or the craft than from the business system that surrounds it. They are articulate because they love talking about it, explaining it, laying bare the art and/or science of it, or championing an improved state of the art for it.

The far horizon of most articulate craftspeople's vision is the edges of their own craft. This limited focus is shared by others who earn trust through service. They are somewhat "tribal," and this limits their market power. Those who earn trust through service are unlikely to steer or change an entire market. As I hope I've demonstrated with the example of my marketing agency friend, limited market power does not translate to limited business success or earning power.

The Leadership Styles of Trust-Earning

Do you know how daunting it is as a writer—how fraught—to try to use the word leadership in a meaningful way? I'm not as concise as Peter Drucker. Repeating my definition: Leadership is helping a group respond to exogenous change or generate endogenous change; management is helping a group optimize the status quo.

The guides in our model are like hands-off managers, but their job is to help clients with a journey of transformation, not optimization. The buyer understands the journey they want to undertake ("I want to climb Mount Everest") but doesn't know the particulars of the journey (left versus right turns, which crevasses are actually dangerous versus merely scary looking). The buyer needs a guide. The consultant demonstrates expertise about this particular journey, and in so doing, they earn the trust of an informed buyer.

Sense-makers make sense of change. They help us think about change and they help us answer questions like:

-

"Is this change a threat, an opportunity, or . . . ?"

-

"How do we contextualize this change? Is it big, small, a curveball, or . . . ?"

-

"What does it mean that this is happening?"

-

"Why is this happening now and not later?"

These questions are milquetoast—almost inert—when expressed in the abstract way I have here, but they take on real urgency and import when they are about relevant, current events for a particular audience. This gives sense-makers (and guides and visionaries) market power; it gives these trust-earning styles the ability to steer a market.

Leaders use the tools of story, narrative, maps, frameworks, ubiquity, status, speaking, and manifestos. They may operate using extensive data, gut feel, or anything in between. They may leverage the status of a single prestigious keynote talk or the ubiquity of 30 podcast guest appearances all released within a few months. They may make skillful use of comfort or shock or anything in between. No matter what tool, method, or style they use, their role is to generate or help us respond to change.

Closed systems need relatively little actual leadership; that is why in our model, the leadership style extends only partially into the region of closed systems. If the closed system is a platform , then the platform owner leads, and everyone else is a user or a vendor. Genuine third-party leadership is a potential threat to the platform owner. If the closed system is a stagnant vertical, there is relatively little change that needs responding to.

You Are Not Locked into One Trust-Earning Style

Again, all models are wrong, but good models are useful anyway. I think this is a decent model, but bear in mind that reality is more fluid than this model depicts.

For example, the management trust-earning style can become a sort of micro-beachhead into leadership. You might earn trust from a small audience through your management expertise, and that existing trust might allow you to serve as sense-maker or guide for that audience—as a leader—in the face of change and novelty. You could think of this as a "battlefield promotion" from manager to leader.

This kind of fluidity is what the real world is like, and so the boxes in our model should always be seen more like fuzzy focal points rather than rigid boxes with impermeable boundaries.

The Importance of Beachheads in Earning Trust

Specialization is a lever to help you get more out of your investment in visibility and augment your ability to earn trust from prospects. Where does the trust-earning leverage come from?

Specialization is a force multiplier . The same amount of modest, journeyman-like trust-earning work applied to a smaller area—fewer people in a smaller, specialized market—produces better results.

Note

37: This is true if you feel that you earned those early wins. If they are the result of luck, they have the opposite effect; they make the long haul seem intolerably long, difficult, and unfair.

Beachheads build momentum . When you experience that first win, that first move beyond your previous trust ceiling, you start to believe in and feel the possibilities that specialization unlocks. These early wins fortify you for the long haul. [37] They help you keep building and investing because you have physical evidence that your investment can pay off. This leads to consistent presence with the market you're focused on, and this consistency helps you earn trust more effectively.

Critically, beachheads shorten learning curves . As independent consultants, we tend to start out business with above-average skill or expertise in a discipline or a craft. I don't know if you'll believe me when I say that no matter how much of an expert you are now, there is a lot more expertise you can cultivate . So much more.

If you know how , you can know why. If you know what , you can see beyond first-order relationships into second and third-order effects in the context of a system. You can understand the patterns that are common to these systems. You can augment gut feel or experience with data. You can move from competence to expertise to mastery.

And if you master one domain, you can scale that mastery into more profitable intellectual property, or you can move up the value chain within your domain.

There is always more expertise you can cultivate. Beachheads are essential to shortening the learning curve. Some of these learning curves look like gaining deeper insight into your market. And some look like deeper forms of the expertise that you are selling your market.

Deeper insight into your market makes you more effective at earning trust, no matter what your trust-earning style is. The social styles benefit from better understanding those they are connecting with, the service styles benefit from better understanding how to serve the market, and the leadership styles benefit from better understanding those they are leading.

Note

38: You would be correct in this belief; even small-scale data collection can help prospects trust you enough to take a bigger risk with you than they would without that data.

39: I can also help you earn more visibility.

Let's say you wanted to augment your expertise in using storytelling to help companies sell innovative products, which has until now been rooted in your own experience, with more objective data. You believe [38] that this investment in acquiring data will help you earn new trust in the marketplace [39] and lead to better, more impactful client work.

You work on formulating the question that will guide your data collection. Which of these questions is the better choice?

-

Does the intentional use of storytelling help companies sell innovative products?

-

What percentage of the companies that have moved from the Visionaries to the Leaders quadrant of Gartner's Magic Quadrant for Cloud Computing in the last five years have CMOs or CEOs that talk publicly about storytelling as a strategic tool?

The first formulation of your research question is too broadly scoped and will delay the experience of traction . The second one offers a beachhead. It will result in an incomplete answer, which could be frustrating, but you will gain access to something that's far more important than completeness; you will trade completeness for momentum . This is a good trade because that momentum will help you efficiently progress toward your ultimate goal of augmenting your expertise in using storytelling to help companies sell innovative products with more objective data. This is just one example of how a beachhead shortens the expertise–cultivation learning curve.

Expertise is especially critical when you are earning trust through the articulate craftsperson, risk reducer, and leadership styles. The faster you can cultivate expertise that genuinely deserves to be called insightful, the better for your trust-earning ability. In other words, the sooner you can land better, more impactful opportunities.

If you use social trust-earning styles, specialization helps you become "monogamous" with your market. That helps with trust-earning.

If you use service trust-earning styles—even if you don't pursue the deepest layers of expertise—specialization shortens the learning curve that lies between your current level of skill and a very high level of competence and consistency in your work. Truly excellent levels of competence and consistency help earn trust.

Note

40: One of reasons you might choose a particular specialization is this heightened level of care, and even if that wasn't why you chose the specialization, you'll tend to develop a caring relationship with the market you've specialized in eventually. Yes, your market will occasionally annoy you, but your interest in their success will overwhelm those occasional annoyances.

And if you use leadership styles to earn trust, specialization and "monogamy" make it unlikely you'll be perceived as a mercenary. You will be more able to embrace the risk of leadership because you'll actually care about those you're seeking to lead, [40] and you'll be willing to speak uncomfortable truths in service of their success.

The social trust-earning styles function without the benefit of specialization better than the others. But they have the least market power and the least versatility across the entire spectrum from closed to open systems.

All the other trust-earning styles benefit from the leverage that specialization offers. In the context of earning new trust from a market, specializing creates a beachhead that leads to gaining genuine insight into the market quicker, and cultivating genuine expertise with which to create value for the market and your business.

The insight and expertise that you cultivate as a result of specialization helps you earn trust more effectively.

Info

- An LLM-generated summary of this book can be found here: LLM-Generated Summary Of TPMfIC

- If you'd like to chat with this book as an OpenAI GPT: https://chat.openai.com/g/g-Ct18XsNSI-indie-consultant-specialization-gpt

- If you would prefer to read this book in Amazon's Kindle ecosystem, or in print: https://a.co/d/aQztpSK

- If you would prefer a DRM-free EPUB copy of this book: https://philipmorgan.lemonsqueezy.com/checkout/buy/06f1179b-3e4a-4e63-a4ee-08c9f166fc34

- If you want to join my email list: https://opportunitylabs.beehiiv.com//)